Remarkable companies are losing to "ordinary" companies. Buffett's rule doesn't work anymore?

In a letter to shareholders in 1989, Warren Buffett articulated one of his investment principles as follows: "It is better to buy a great company at a fair price than an ordinary company at a great price". This became one of the most popular statements of the legendary investor. More than 30 years later, analysts at investment firm Macquarie Group say Buffett's rule doesn't stand the test of time. Why do they argue with the Wall Street guru and what do they advise investors to pay attention to?

What is the "Buffett rule"

Buffett adheres to the classic value approach, which involves looking for companies that have a market price below fair (intrinsic) value. His strategy is to find undervalued companies with strong fundamentals - high return on equity, low debt load and strong cash flow. Buffett favors simple business models and transparent management teams, avoiding complex structures and overvalued stories.

As Berkshire Hathaway's portfolio showed at the end of the second quarter, Buffett still bets on quality companies, especially those with moderate valuations, and avoids expensive and high-risk growth stocks. In the second quarter, for example, Berkshire bought more than 5 million shares of insurer UnitedHealth, taking advantage of its falling stock price.

How this strategy was tested

Macquarie Group analysts (Oninvest has their research) have developed their own model for quantitative assessment of business quality. It helps determine how "great", in Buffett's parlance, a company really is. Profitability, sustainability of financial results, growth dynamics and capital management are taken into account. The results are compared to a valuation of value - that is, how much the stock is trading above or below its fair or intrinsic price.

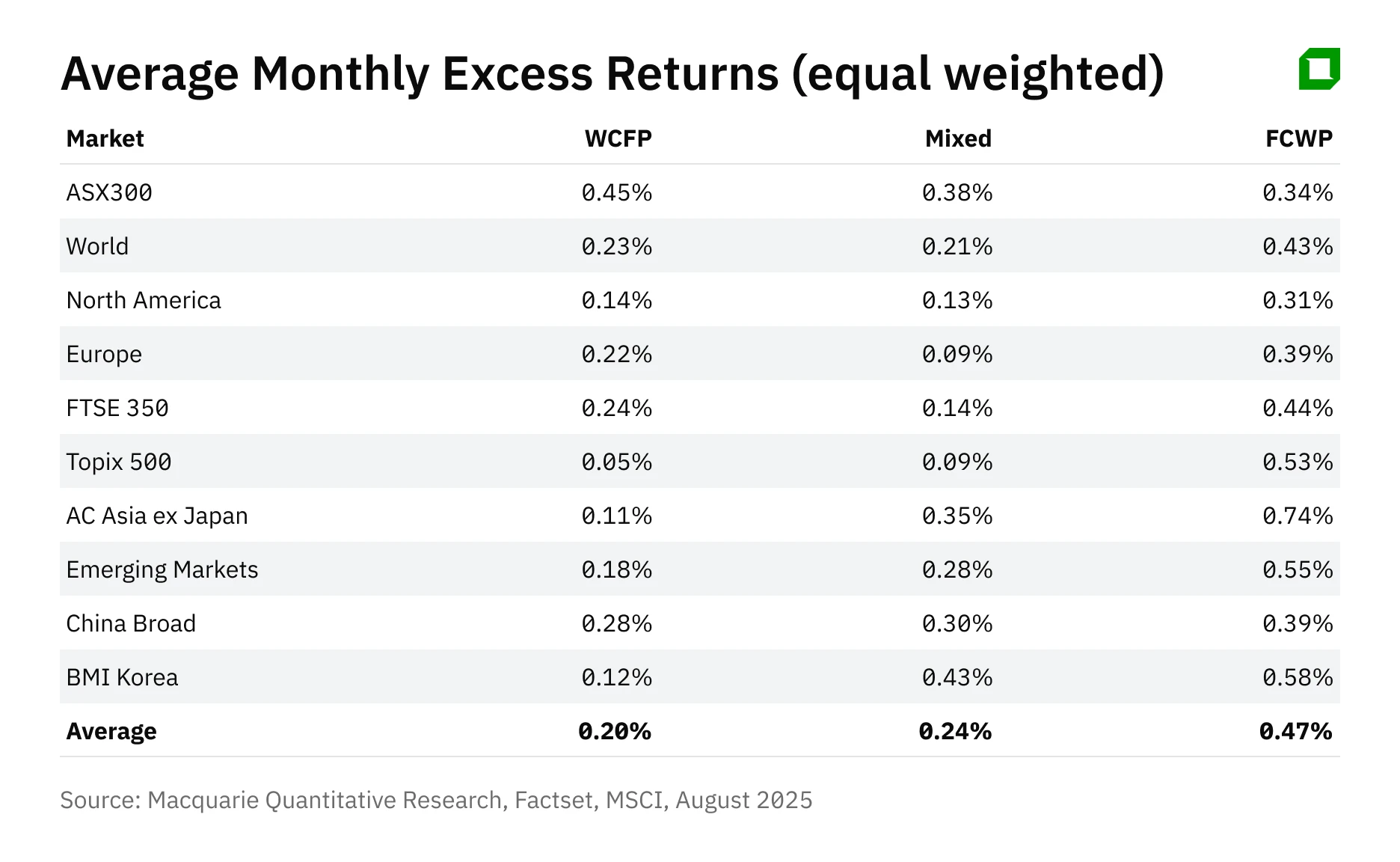

So the researchers identified fundamentally cheap stocks - both high quality and undervalued by the market - and divided them into three groups:

- "Wonderful Companies, Fair Price," or WCFP, is the kind of company Buffett has traditionally favored;

- "common companies with a remarkable price" (Fair Company, Wonderful Price, or FCWP) - the kind Buffett recommends avoiding, even if their price looks attractive;

- and the Mixed category.

Then the analysts conducted a backtest: they took 30 years of data on the world's ten largest markets - from America and Europe to emerging markets - and modeled what Buffett's portfolio would look like if he bought only companies in one category. To keep the experiment clean, Macquarie Research rebalanced the portfolio every month - as if the investor were regularly updating his investments.

What the test showed

Contrary to Buffett's principle, investing in "ordinary" companies at "remarkable" prices has been more profitable in the long run, says Macquarie Research.

The results of the study showed that in nine out of ten global markets, Buffett's preferred "great" companies purchased at a fair price delivered lower returns than the mediocre companies he rejected, purchased at a very low price. The only exception was Australian stocks in the ASX300 index.

For example, Macquarie included Bank of China in the basket of "ordinary companies with a remarkable price": according to the model, it belonged to the "cheap" companies, but at the same time showed high profit stability and low risk. The same group included Japanese Mitsubishi HC Capital and Australian Amcor, which were undervalued by the market. The combination of a low price and acceptable sustainability or growth metrics allowed these and other portfolio companies to outperform "great" businesses bought at a fair price.

The outweighing of "ordinary companies" in the long term can be explained by the higher growth potential of multiples, says Macquarie Research. In other words, "ordinary" businesses bought at the bottom of valuations get more room for revaluation by the market than "remarkable" companies that are already trading closer to fair value.

But at the same time, the analysts say, both strategies have been profitable in the historical perspective. At the same time, the "great companies" retain an important advantage: they behave more stable in periods of turbulence. Macquarie Research researchers concluded that when risks grow or the economy goes into recession, it is "great companies" that demonstrate a protective character. In recovery and expansion phases, "ordinary companies" come out ahead, overtaking the market on the wave of risk demand.

What an investor should do

The analysts emphasize: the results of their study do not mean a complete abolition of the Buffett formula. The test showed not the absolute superiority of one basket over another, but rather the dynamics of leadership: "ordinary companies at a great price" are stronger on the long horizon and in growth phases, "great companies at a fair price" are a more reliable "safety cushion" in case of a crisis.

In essence, we are talking about two strategies with different profiles: one helps to overtake the market in recovery phases, while the other provides protection in a crisis. The authors conclude that it is impossible to mechanically replace Buffett's principle with the reverse one - in the long term, it is important for investors to take both logics into account.

But we should not forget that the figures, even if for 30 years, reflect only part of the picture. Although Macquarie's analysis is interesting, it cannot be considered a "pure" test of Buffett's hypothesis, CNBC notes. The famous statement of the "Oracle of Omaha" is not a strict quantitative law, but rather a philosophy based on the concepts of "margin of safety" and long-term compounded capital growth. Macquarie's quantitative approach does not include intangible factors, such as brand awareness, nor does it take into account Buffett's main message to investors: their goal should be sustainable capital growth while minimizing the risk of ruin.

This article was AI-translated and verified by a human editor