Stability is the enemy of growth: lessons from Nobel laureates on the 2025 economy

The strongest obstacle to technological progress is the defense of the position of those who have succeeded in the past. Economic growth is a conflict that requires the destruction of what has been created before. For growth to become sustainable, we need social mechanisms that support innovation. These are the main ideas of the winners of the Nobel Prize in Economics 2025.

The Nobel Committee usually seeks to diversify the economics prize by field of science. There is no such thing as giving it two years in a row to scientists working in the same research field, wrote University of Chicago professor Konstantin Sonin before the announcement of the 2025 laureates.

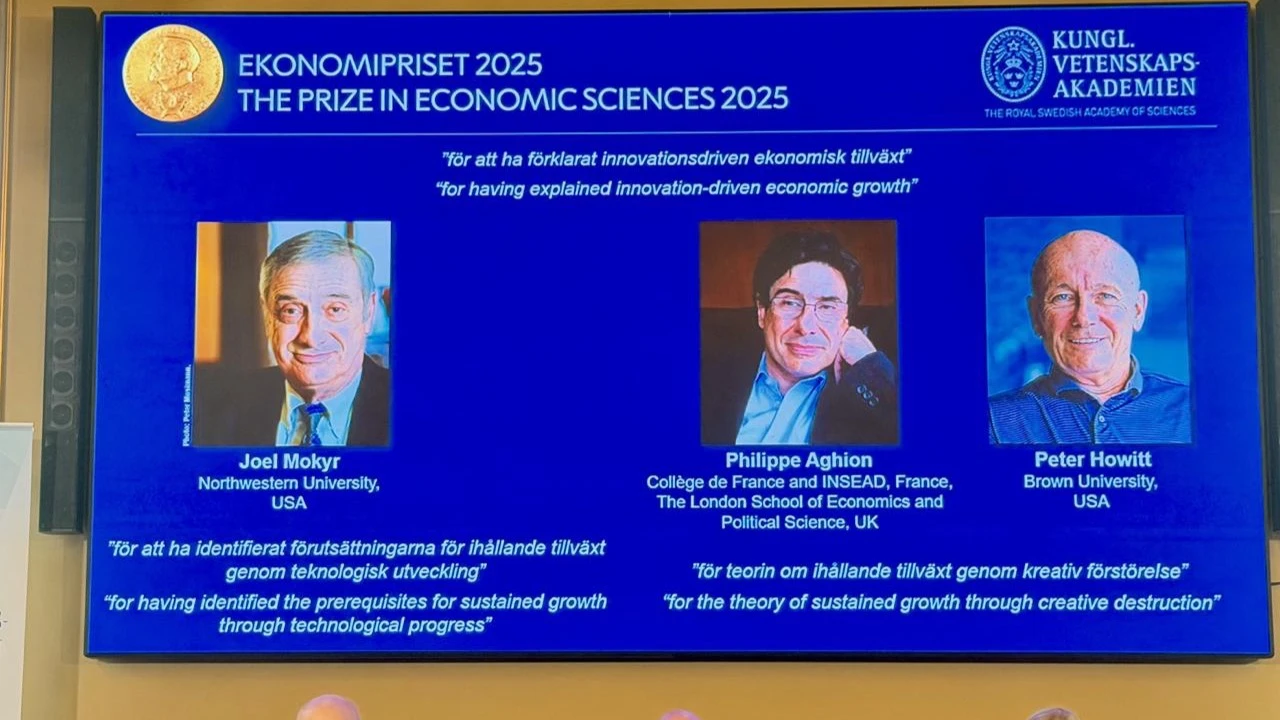

But this year, the Nobel Committee, which likes to emphasize its complete unpredictability, broke this principle as well. As in 2024, the prize was awarded to economists researching the mysteries of long-term economic growth, the role of innovation, creative destruction and institutions. In 2024, the winners were Daron Adjemoglu, James Robinson and Simon Johnson, and in 2025, Joel Mokyr, Philippe Agyon and Peter Howitt.

Innovation and technological progress produce sustainable economic growth by forcing people to abandon previously invented products and technologies and create new ones. With such a formula, referring to Joseph Schumpeter's idea of creative destruction, the Nobel Committee has paired Mokyr, Aghion and Howitt. Half of the prize will go to Mokyr, who works at Northwestern University (USA) and Tel Aviv University. Aghion is at Collège de France, INSEAD and the London School of Economic and Political Science, and Howitt is at Brown University.

Change or die

The main merit in popularizing the idea of creative destruction belongs to Schumpeter, who in 1943 published the book "Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy". The most successful entrepreneurs, he wrote, are innovators who come up with new products and production technologies. They prove to be more efficient and remove old ones from the market: this is the key engine of capitalism's development.

Creative destruction is also important for individual companies - periodically they need to abandon even their successful products to keep up with competitors in creating new ones.

The idea of creative destruction is also applied in economic history - for example, Adzhemoglu and Robinson showed that economic growth can turn to stagnation and decline because ruling elites block the process of creative destruction. The elites try to protect their position and end up stopping the development of the country.

Regulation always favors those already in the market, so the more heavily the government regulates firms, the less innovation there is in the economy, Agyon demonstrates using France as an example.

Agyon and Howitt, who began working together in 1987-1988, are the brightest continuators of the Schumpeterian tradition, expressing it in modern economic language. In their joint books The Economics of Growth (2009), Endogenous Growth Theory (1997), in an article on Schumpeterian growth theory and other works, they show that economic growth is the result of internal rather than external factors (innovation, investment in human capital and knowledge).

Aghion's theme of creative destruction is probably hereditary. His mother, the couturier and founder of the fashion house Chloé, coined the term prêt-à-porter, was Carl Lagerfeld's employer, and said of her early career in fashion: "Everything had yet to be invented, and that was exciting to me".

The models of economic growth created in the middle of the 20th century assumed that the development of technology and scientific progress affect the economy, but unilaterally. It was believed that the economy could not influence the speed of scientific and technological discoveries. In this construction, the causes of economic growth were understood as external, exogenous, and economic policy was not considered very significant for growth, because it is difficult to influence external factors.

In contrast, the endogenous theory of growth (an important contribution was made by two other Nobel laureate economists, Paul Romer and Robert Lucas) attributes it to internal causes. This theory suggests that the economy and technology influence each other: technological knowledge, like other forms of capital, can be accumulated and put into production. The former requires more spending on research and development, the latter requires competition. This theory shows that economic policy is crucial: if the factors determining growth are internal and not externally determined, then policy can influence them.

Some countries are good at it. Developing countries, Howitt writes, should not be called the poorest countries, but the richest and most successful: they are the ones who are constantly and painfully changing.

On the contrary, the lack of permanent transformation is characteristic of the poorest countries at the pre-industrial stage of development. "Change or die" (i.e. get off the path of economic growth) is the pathos of Schumpeterian theory: difficult and painful changes are needed for permanent prosperity.

It is very difficult for individual entrepreneurs, companies, economic and political elites to change: to do so, they have to give up the position they have already gained.

Healing competition

No one would voluntarily take such a step: there are no fools. Therefore, the key condition for sustainable growth, apart from the country's inclusion in global trade and stimulation of technological innovation, is to maintain a high level of competition. This is what makes the whole system change. The Aghion-Howitt model links the decisions of individual economic agents and economic growth as a whole. By investing in new technologies for the sake of profit, entrepreneurs contribute to technological progress and growth of the national economy (it depends on the speed of replacing old goods with new ones).

Agyon develops this model in numerous papers. In one of the most recent, he shows that new firms enter the market with new products and technologies and remain committed to what made them successful. But over time, it becomes increasingly difficult to improve on what was previously introduced. Firms complete their life cycle, face a shortage of ideas, and leave the market.

Economic growth is always the result of a conflict of interests of different market participants. Therefore, by protecting the interests of existing producers, governments hamper economic growth. Other things being equal, new companies have more incentives to develop new goods and services than those already on the market.

The development of new products deprives owners of existing companies of their market share. The greater the political weight of "losing" businessmen, the more the government will protect them, increasing the costs of newcomers to introduce new products and technologies and thus hindering growth.

On the contrary, the higher the competition, the more companies spend on R&D and the more innovations they produce, Agyon proved. He is therefore concerned about the decreasing level of competition in the U.S. and especially in the European economy. This has the potential to increase rent incomes, slow innovation and technological lag.

The miracle of economic development

Innovation, technological progress and prosperity have characterized only the last centuries of human history. Technologically progressive societies are the exception, not the rule, while the norm is "stagnation and equilibrium," as Joel Mokyr, a historian of technological and economic development, likes to emphasize.

His books "The Lever of Wealth. Technological Creativity and Economic Progress," "The Enlightened Economy. Great Britain and the Industrial Revolution 1700-1850" and "The Gifts of Athena. The Historical Origins of the Knowledge Economy."

The forces opposing technological progress have almost always been more powerful than those pushing for change. Mokyr compares technological progress to a fragile and vulnerable flower, created by a random combination of factors and highly sensitive to the economic and social environment. Progress should not be taken for granted - it can easily be halted by small external changes.

Mokyr puts knowledge, not labor, capital, or institutions, at the center of economic growth. For growth to become sustainable, society had to establish an interaction between two types of knowledge: scientific knowledge of the laws of nature improves technical knowledge about how to make an object, and it helps drive science forward.

This is exactly what happened in Great Britain and Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries: it was not individual inventions that provided the economic breakthrough, but the emergence of social mechanisms that stimulated innovation.

Mokyr shows how a marketplace of ideas emerged in Europe, opening up opportunities for inventors and giving rulers incentives to compete for talent. This made growth sustainable, self-sustaining. It is based on knowledge and innovation, which enhances growth and spurs new knowledge.

At the end of 2025, Mokyr will publish a book with historian Avner Greif and economist Guido Tabellini. It argues that throughout the second millennium, the different trajectories of the economies of Europe and China were caused by the different forms of social organizations that emerged there in the pre-industrial era. In China, these were clans based on kinship and compatriotism, while in Europe they were corporations (universities, guilds, and partly even monastic orders), which made possible the emergence of self-governing cities.

This difference influenced the difference in political institutions and mechanisms of production of public goods: in China, an authoritarian system was in place that stifled innovation, while in Europe the scene was prepared for the industrial revolution (Mokyr's previous books are devoted to it).

He is writing his next book with Agyon (they have not worked together before) and hopes it will sell well now that he has won the Nobel Prize.

This article was AI-translated and verified by a human editor