The power of creative destruction: why the Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded

On Monday, October 13, the Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to scientists who in their research provided "an explanation for the economic growth provided by innovation". New and breakthrough technologies that change the world and increase prosperity are impossible without competition in the marketplace of ideas, the laureates showed. Yes, they are disruptive. But fighting them for the sake of stability leads to stagnation and degradation, which has happened many times in world history.

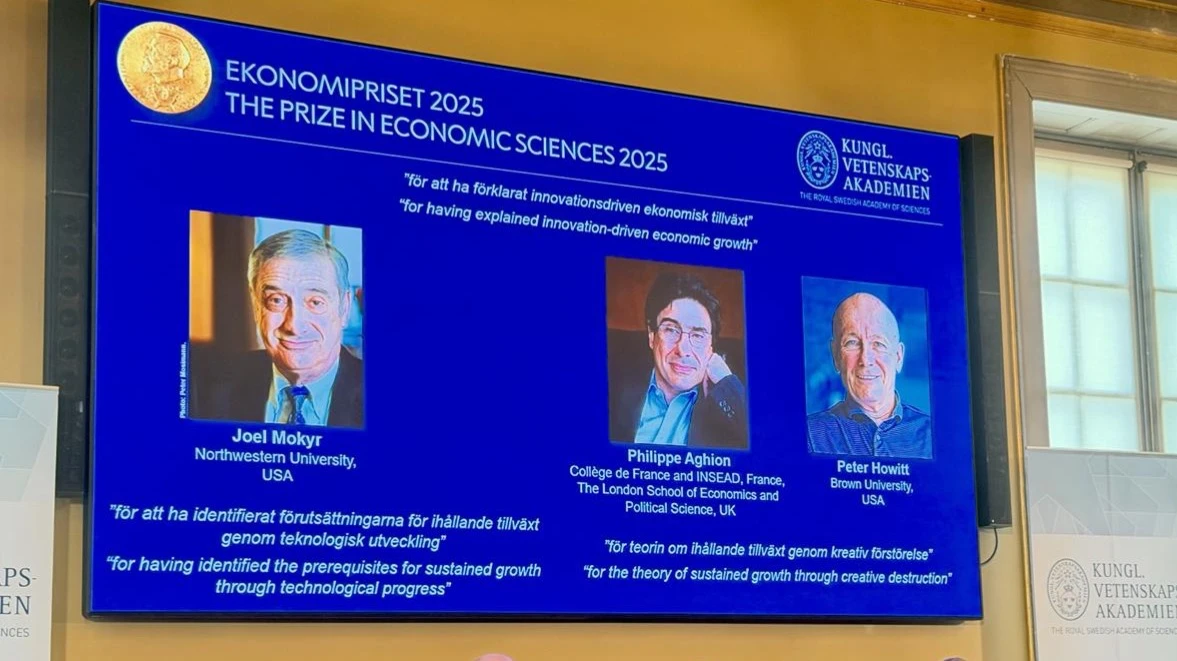

Joel Mokyr, an economic historian and professor at Northwestern University in the United States and Tel Aviv University, was awarded "for identifying the preconditions for sustainable growth through technological progress," the Nobel Committee said in a statement. He will receive half of the prize - it amounts to 11 million Swedish kronor (about $1.2 million). The other half will be shared by Philippe Aghion (Collège de France, INSEAD and the London School of Economics) and Peter Howitt (Brown University in the US). They are awarded "for their theory of sustainable growth through creative destruction".

Challenge to stagnation

Almost all of its history, mankind has lived in poverty. Somewhere, prosperity was sometimes improved - for example, in ancient Rome, the medieval Arab world, Florence, Venice - but progress did not extend to the whole of humanity and faded over time in these countries and regions. China, for example, was the richest and most technologically advanced country in the world in the first half of the second millennium AD, but in 1950 the average Chinese person was poorer than in that era.

Stagnation has been the norm throughout most of human history, the Nobel Committee said in a statement: "Despite important discoveries that have sometimes led to improved living conditions and higher incomes, the rate of [economic] growth has always leveled off in the end."

The situation changed thanks to Western Europe. It was in the late 18th and early 19th centuries that it was able to initiate an unprecedented growth of prosperity that spread throughout the world.

"Over the past two centuries, the world has experienced sustained economic growth for the first time in history. It has lifted vast numbers of people out of poverty and laid the foundation for our prosperity. This year's laureates <...> explain how innovation provides the impetus for further progress," the Nobel Committee said.

According to his explanation, Mokyr showed: for innovation to feed on each other, it is necessary not only to know that something works, but also to give it a scientific explanation. The latter was often lacking before the Industrial Revolution, making it difficult for new discoveries and inventions to emerge and be put into practice. In addition, according to Mokyr, it is essential for society to be open to new ideas and to allow for change.

In turn, Agyon and Howitt, who also studied the mechanism of sustainable growth, proposed in a 1992 paper a mathematical model of what economist Joseph Schumpeter called "creative destruction." When a new and better product comes on the market, companies selling old products suffer losses, the committee said in a statement: "Innovation represents something new and is thus a creative phenomenon. However, it is also disruptive because a company whose technology becomes obsolete loses the competition."

Mokyr represents the camp of proponents of the "idealist" theory of growth, former Bank of England senior adviser and economics professor Tony Yates noted in a column in the Financial Times. In it, culture or ideology is the deciding factor, as it either promotes or hinders the development of a growth mindset and social progress. Agyon and Howitt, on the other hand, develop a "materialist" theory where incentives are based on material circumstances, such as the availability of labor and raw materials, or institutions, Yates noted.

Ideas that undermine stability

"The 'idealism' of his theory is postulated by Mokyr in the very first sentence of his book "The Enlightened Economy. Britain and the Industrial Revolution 1700-1850": "Economic change in all epochs has depended more than many economists believe on what people believed."

Ideas, according to Mokyr, are a fundamental component of change. And a competitive marketplace of ideas is a critical factor in enabling societies to sustain economic growth and prosperity, he said in an interview: "We know that competitive markets are more dynamic, more progressive, and generate more important innovations. This competition is what makes the difference in development.

In Europe, largely due to its fragmentation (geographical, political, religious), a competitive marketplace of ideas had already emerged by 1600. And this played a fundamental role in putting Europe on the path to modern economic growth less than two centuries later.

Meanwhile, many societies stopped developing when advances in science and technology made it possible to reach a certain level - stability became the priority: "Controversial views were no longer encouraged, and people who disagreed with traditional ones were punished. This is what happened in China, in the Islamic world in the Middle Ages.

A similar picture was observed in the USSR, where questioning generally accepted positions could get you thrown in jail, Mokir noted: "Some areas necessary for the state were developing - aerospace, military technology, and in these areas Russia was able to compete with the West for a long time. But many other areas fell by the wayside because the state was not interested in them. And in the West, if someone wants to do something, he goes and does it. Invent the Internet, invent plastic windows, engage in genetic engineering. If it works - please, why not? This is the unique feature of an uncontrolled competitive marketplace of ideas. And in a totalitarian society, this is not the case.

Totalitarianism is the main enemy of progress; it largely establishes a monopoly in the marketplace of ideas, Mokyr believes.

AI as an agent of change

New ideas and technologies undermine established ways of doing things, and "the laureates show how creative destruction creates conflicts that must be resolved in a constructive manner, otherwise it will be blocked by incumbent companies and interest groups that risk being disadvantaged," the Nobel Committee said.

There have been many such examples in history, Mokyr cites them in his book The Lever of Wealth.

In 1299, for example, the Florence authorities banned bankers from converting to Arabic numerals. In 1397, manufacturers of pinheads, produced by hand in Cologne, achieved a legislative ban on the use of machines for their stamping. At the end of the 15th century, scribes in Paris prevented the installation of printing presses in the city for 20 years. In 1561, the city council of Nuremberg decided to imprison anyone who would manufacture and sell a new lathe previously invented by a local resident. In 1579, the city council of Danzig may have ordered that the inventor of the tape-weaving loom be secretly drowned.

Many are now worried about the effects that artificial intelligence could have on the current economy and jobs. In this situation, "Schumpeterian growth theory is particularly important," Sascha Steffen, professor of finance at Frankfurt School of Finance and Management, told the FT.

The laureates' ideas, he said, "suggest to policymakers and investors how to turn AI and the transformational challenges it presents into sustainable, inclusive growth - by supporting experimentation, enabling market entry, and rapidly moving capital from legacy industries to innovative ones."

"Thanks to AI, it will be easier than ever to find ideas, so it has a lot of growth potential," Agyon said at a press conference in response to a question from reporters. - The challenge is to capitalize on that potential, and that's where antitrust policy is important."

As for concerns like AI will put a lot of people out of work, Agyon noted that predictions of mass unemployment made by critics of the change in the past have not come true. "That never happens," he added.

Mokyr is optimistic about the possibilities of AI, seeing it as a new stage in a story that began with the first computers in the 1950s and 1960s and continued into the 1980s and 1990s with the advent of the personal computer. "It will be a very handy tool," The Wall Street Journal quoted him as saying. - It will aggregate information at a staggering rate. It will make us more productive and give us much better access to knowledge."

This article was AI-translated and verified by a human editor