Brake or stimulus: will Kazakhstan turn OPEC+ restrictions into a driver for development?

Kazakhstan's oil sector has been stagnating for several years, partly due to the need to comply with OPEC+ quotas, which the country does not always strictly adhere to. In 2026, production will have to be restricted even further to compensate for past excesses. But can Kazakhstan use this as an incentive for development? Kirill Lysenko, an analyst for sovereign and regional ratings at Expert RA, answers this question.

Violations and consequences

In 2025, Kazakhstan was repeatedly named one of the most notorious violators of OPEC+ production quotas. With an average quota of 1.51 million barrels per day, the country produced approximately 1.74 million barrels per day. A similar situation arose a year earlier, with the country regularly exceeding the quotas set by the oil cartel.

All this will have a delayed effect on Kazakhstan—in 2026, it will be forced to compensate for overproduction before OPEC+. Judging by the joint OPEC plan published in early December 2025, Kazakhstan will have to reduce crude oil production by approximately 12.7 million tons relative to its quotas in the first half of 2026.

It is possible that Kazakhstan will continue to fail to fully comply with the cartel's requirements. One reason for this is that international consortia, including Chevron, Shell, and Exxon Mobile, are actively involved in the country's oil sector. The Kazakh authorities have limited influence over them. This primarily concerns three mega-projects: Tengiz, Kashagan, and Karachaganak. In 2024 alone, they accounted for more than 60% of the country's oil production.

Forced cooperation

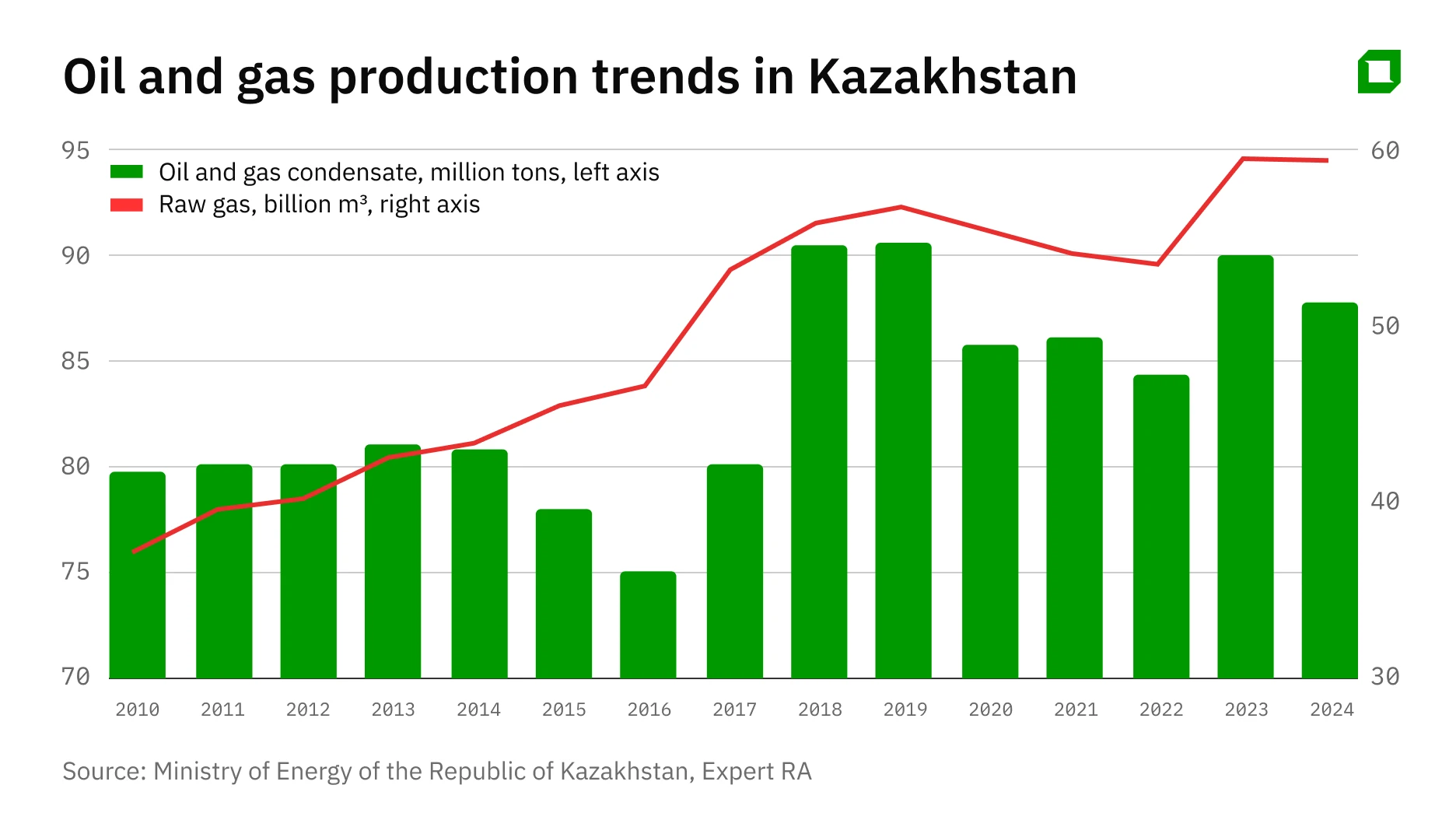

The need to comply with quotas set by OPEC+ to balance supply and demand in the global market has been one of the reasons why oil production in Kazakhstan has stagnated over the past five years, following rapid growth in 2017–2019. Weakening demand on global markets and scheduled maintenance work at key fields also had an impact.

A logical question arises: why does Kazakhstan need OPEC+ membership? The republic joined the alliance in 2016. It was a difficult period for oil exporters—the average annual price of Brent was $43.67, with a low of just over $30 per barrel in January.

The collapse in oil prices required coordinated measures to stabilize the market.

However, joining OPEC+ did not prove to be a panacea: the agreement did not create equal incentives for all participants to comply with the agreements. Since there are no sanctions for violators, the only deterrent is essentially a general response by other OPEC+ participants to violate the agreement. And this leads to a chain reaction of falling oil prices.

However, the heavyweights of the alliance (primarily Saudi Arabia and Russia) are not prepared to trigger a spiral of falling prices because of Kazakhstan, whose share of global production is about 2%. This means that the country can violate OPEC+ agreements without any losses for itself, simply promising to compensate for excess production later.

Of course, a sense of proportion is needed here too: serious violations of agreements could lead to the country's opinion no longer being taken into account when new decisions are made. This carries reputational risks, with possible consequences for investment and diplomatic relations. However, this is also the case with formal withdrawal from the association.

How can Kazakhstan cope with OPEC+ quotas?

Kazakhstan's position in April this year was formulated by the country's Minister of Energy, Yerlan Akkenzhenov: "We will try to adjust our actions. If our partners... are not satisfied with these adjustments, then we will again act in accordance with national interests, with all the ensuing consequences."

In such conditions, when opportunities for active development through increased production are objectively limited, Kazakhstan's primary task is to increase the added value per unit of extracted raw materials (and not necessarily its own). In other words, the key reserve for growth lies not in production, but further down the technological chain—in processing, transportation, and petrochemicals.

Currently, only about 23% of the oil produced is processed domestically—the majority is exported abroad in its raw form.

At the same time, domestic demand for petroleum fuel is growing steadily: over the past 10 years, domestic consumption of gasoline and diesel fuel has increased by 31% and 16%, respectively. Meanwhile, Kazakh refineries are operating at over 90% capacity—they are already working at virtually full capacity.

This means that in order to continue meeting domestic demand and developing the oil refining sector, the country needs to actively attract investment and new projects.

However, a favorable environment is necessary for a robust investment process, including in terms of pricing conditions that are acceptable to potential investors.

And there are problems with this. In Kazakhstan, the cost of basic types of fuel for the population is regulated. In January 2025, the country's Ministry of Energy stopped setting maximum wholesale and retail prices for gasoline and diesel fuel and let them float freely. But by October, liberalization had been replaced by a price freeze.

OPEC+ restrictions affect not only oil but also gas production in Kazakhstan: almost all of it (95%) is associated gas. This means that when the country curbs oil production, gas production automatically decreases as well. Increasing supplies is also difficult because a significant portion of the gas (about 40%) is pumped back into the fields to maintain pressure in the oil wells.

All this exacerbates the issue of gas security. Due to rapid growth in demand amid stagnant production, Kazakhstan is rapidly moving toward becoming a net gas importer, making stable import supplies critically important.

Kazakhstan's physical trade balance for natural gas is steadily declining: from 9.8 billion cubic meters in 2019 to 1.5 billion in 2024. In 2024, the country exported 8.7 billion cubic meters of natural gas, mainly to China and Russia. (For comparison, 10 years earlier, Kazakhstan exported 11 billion cubic meters of gas). At the same time, the country imported 7.2 billion cubic meters of gas from Russia and Turkmenistan.

Are OPEC+ commitments a blessing or a curse for Kazakhstan?

In the short term, the need to comply with OPEC+ requirements is a negative factor for Kazakhstan. Even if there are opportunities to increase production, the cartel's quotas limit production and exports, reducing the return on funds already invested in projects and increasing the budget's dependence on oil prices. This leads to lost profits and exacerbates the conflict between national interests and obligations under the agreement.

However, in the long term, the effect on Kazakhstan is likely to be positive. Production restrictions act as a "collar" on an economy prone to reproducing a growth model focused on the raw materials sector and its export performance.

The real weight of the oil and gas sector in Kazakhstan's economy over the 10 years to 2024 has already fallen from 21.6% to 17.2%, while output in this sector has grown by a quarter. Kazakhstan's oil and gas sector is growing more slowly than the rest of the economy.

In addition, such restrictions are pushing the country towards the development of processing, petrochemicals, and infrastructure. Between 2022 and 2024, the volume of petrochemical production in Kazakhstan has already grown 2.84 times, to 540,000 tons.

New large oil and gas chemical enterprises are currently under construction. In 2026, the country will see the emergence of alkylate and polyvinyl chloride production facilities. In 2027, two methanol plants with a total capacity of 230,000 tons per year and a butadiene plant in the Atyrau region with a capacity of 186,000 tons per year, 75% of which belongs to Tatneft, will be commissioned. In 2029, a Silleno polyethylene plant with a capacity of 1.25 million tons per year will be launched. This is a project of KazMunayGas with China's Sinopec and Russia's SIBUR.

These are just some of the new projects in the field of petrochemicals. They will enable Kazakhstan to avoid the resource curse and transition to a more sustainable industrial model of economy.

This article was AI-translated and verified by a human editor